Human history is basically just a long list of people doing incredibly sketchy things, just for a paycheck. Before we had OSHA, or even a basic understanding of germs, “workplace safety” was mostly just trying not to die before the lunch whistle.

The Jobs We Left Behind

While many of these roles started in Europe, they defined the working world that eventually shaped the early American workforce. We’re talking about a time when your health wasn’t just at risk; it was expected to be traded for a wage.

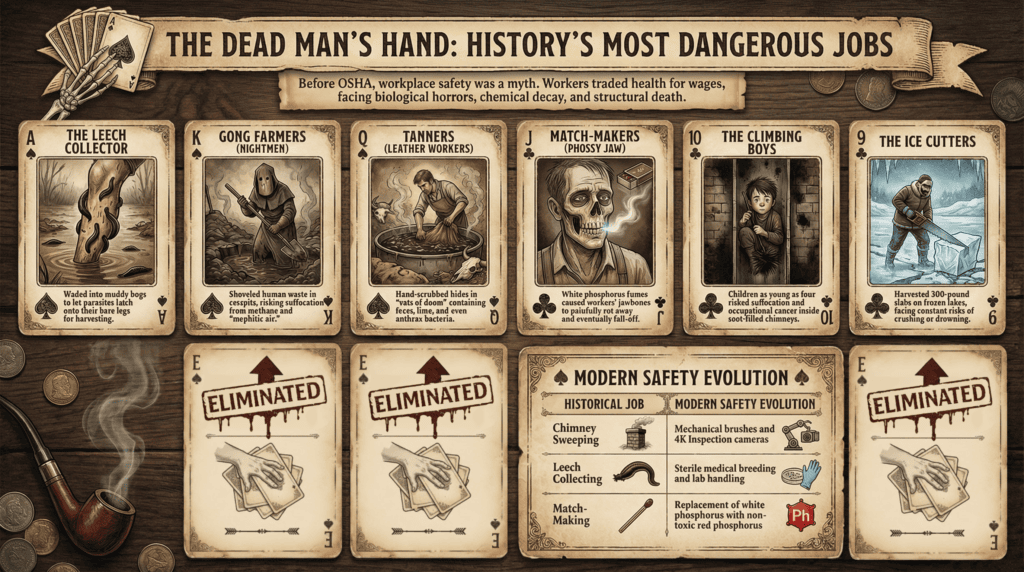

Leech Collector

Long before you could just grab a pill at the pharmacy, if you had a fever or were just feeling “off,” the doctor’s first thought was usually to drain some of your blood. This created a massive market for leeches.

The job of a Leech Collector was simple, in a horrific way: you’d wade into a muddy bog, wait for the leeches to latch onto your bare legs, and then pull them off to sell. It was a human buffet. Beyond the obvious “being eaten alive” part, the real damage was slower. Constant bites meant constant open wounds. Stagnant water meant infection. Add in whatever else was living in that swamp, and you had a steady pipeline of disease that made this one of the most dangerous jobs of the time.

We still use leeches today, just not harvested from someone’s shinbone in a bog. They’re bred in sterile medical facilities now, and handled by sterile processing technicians like surgical tools instead of parasites.

Tanners (Leather Workers)

Living anywhere near a tannery in the 1800s was pungent… You definitely smelled it before you saw it. Turning raw hide into leather was a brutal, messy, corrosive, and chemically aggressive way before we even had the words to describe ‘chemical exposure.’

Tanners spent their days elbow-deep in “vats of doom” filled with lime, alkaline salts, and, believe it or not, pigeon or dog feces to soften the skins. The risk wasn’t just the smell. Workers were exposed to anthrax from the hides and chronic respiratory issues from the fumes. It was a slow-motion disaster for your lungs and skin. Today, chrome tanning and automated tumblers have taken the “hand-scrubbing with manure” out of the equation, though it remains a high-regulation industry for a reason.

Gong Farmers and Nightmen

Before modern plumbing, someone had to deal with the… fallout. “Gong Farmers” (or Nightmen in the US) had the unenviable task of cleaning out cesspits and privies, usually under the cover of darkness.

This wasn’t just a gross job; it was a lethal one. Digging around in human waste meant constant exposure to “mephitic air” which is basically a deadly buildup of hydrogen sulfide and methane. Workers could be overcome by fumes and suffocate in seconds or die later from a laundry list of waterborne diseases, like cholera. This job was dissolved as soon as we realized that pipes and sewers were a better alternative than asking someone to shovel waste into a cart at 3:00 AM.

Chimney Sweepers

Mary Poppins and pop culture might have made the job look whimsical. But, it wasn’t. The real version was actually anything but. Chimneys were tight, crooked tunnels layered with thick soot and toxic residue. The solution? “Climbing boys.”

Most were children. Some barely four years old. They were sent straight up inside those flues to scrape creosote by hand. If they slipped, got wedged in a bend, or couldn’t breathe through the soot, there wasn’t much margin for rescue. Over time, many developed what doctors later identified as “Sweep’s Cancer,” one of the earliest documented occupational cancers. It wasn’t until the mid-1800s that child labor laws and mechanical chimney brushes fixed the problem. Today the job looks even more different: Powered vacuums, inspection cameras, and long rods.

Matchmakers (“Phossy Jaw”)

In the Victorian era candles lit the way, so everyone needed matches. To make them, mostly women and teenagers spent 12-14 hours a day, 6 days a week, dipping little wooden sticks into giant vats of white phosphorus. The fumes were deadly and disfiguring.

Over time, the phosphorus would cause the jawbone to literally rot away. It was visible, painful, and usually ended up being fatal. This was actually one of the first times in history that a job, that was generally seen as one of the most dangerous jobs of its time, pushed its workers to do something BIG…

The low wages and terrible working conditions led to the 1888 Matchgirls Strike. It was one of the first major successes for unskilled, female workers; and lasted approximately three weeks. Eventually, it led to the ban of white phosphorus and replaced it with, the much safer and less toxic, red phosphorus that we still use today. It’s a perfect example of an industry getting completely reshaped by its people standing up for themselves.

The Ice Cutter

Before the “magic” of the refrigerator, if you wanted a cold drink in July, someone had to go get it from the winter. Ice cutting was a massive industry in the early 1800s. Men would take massive saws out onto frozen lakes to harvest blocks of ice.

The danger was literally all around you. Falling in the icy water was only one of the risks. Horses broke through. Ramps could fail. And a 300-pound ice slab sliding the wrong direction can do serious damage. When mechanical refrigeration hit the scene in the early 20th century, the need for large-scale ice harvesting ended. Now, the most dangerous part of getting ice is the occasional brain freeze.

Trading the Danger for Data

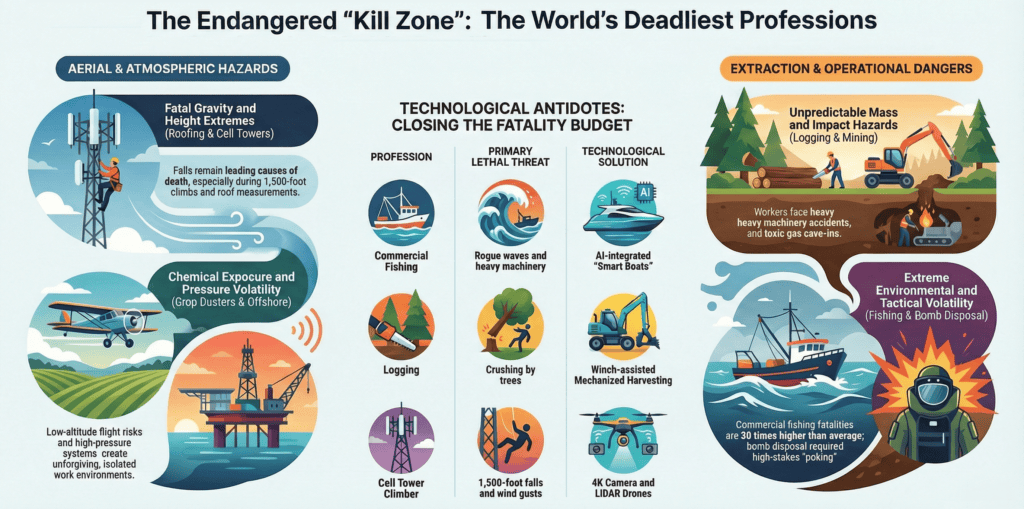

We haven’t completely wiped-out workplace risk for the most dangerous jobs, but we’ve changed the “how.” We’ve traded the bone-rotting phosphorus of the 1800s for high-voltage towers and deep-earth extraction. The goal is simple: Get people out of the “Kill Zone.”

Jobs that used to be a coin toss for your safety are being completely reshaped by new tech that used to seem like science fiction.

Cell Tower Climbers

For years, this was a staple of the most dangerous jobs list. You clip into a harness and haul yourself 1,500 feet into the air, in the wind, just to see if a bolt was loose or if a bird has made a nest in a transmitter. One equipment failure or a sudden strong gust, and that was it.

But it’s being completely restructured right now. Drones. They don’t need to risk their life just for a routine inspection anymore. A drone with a 4K camera and LiDAR does the same job in less than twenty-five minutes. No risk. The technician stays on the ground with a tablet.

Routine “climb-to-look” inspections are basically dead. Climbers are still needed for the actual repairs, but the sheer volume of high-risk climbs has plummeted since we have robots doing the scouting first.

Underground Miners

Mining is one of the most classic dangerous jobs. Workers feared cave-ins, used birds to test for toxic gas, and handled heavy machinery accidents. It all used to be part of a Tuesday routine. It was brutal work and it took a massive toll on all parts of the body.

Now-a-days mining is being completely reshaped by safety, through automation. We’re talking about driverless haul trucks the size of houses and robotic drilling rigs that operate deep underground while the operator sits in a climate-controlled office miles away. AI sensors now “sniff” the air for methane and “listen” to the rock for signs of a collapse way before any person could ever pick it up. It hasn’t been completely phased out yet, but the days of “canaries in a coal mine” are officially a thing of the past.

Offshore Rig Workers

If you’ve ever set foot on an offshore platform, you know it’s one of the most unforgiving places… Anywhere. They don’t leave much room for error before something bad happens. High-pressure systems, volatile chemicals, and the constant threat of fire with open ocean in every direction. It can be… Isolating.

“Digital Twins” are the secret weapon. Before technicians even touch a valve on a rig, they’ve already practiced the move a dozen times on a virtual replica that reacts exactly like the real thing. On the actual platform, we’re seeing robots take over the “annoying, dirty, and dangerous” tasks. Sub-sea-robots can handle pipeline repairs at depths that would crush a person, and autonomous drones fly into cramped, hazardous areas to “sniff” for gas leaks with infrared sensors. The jobs are moving from a FIFO “wrench-turner” to “system-monitor,” which is always a much safer place to be.

Logging and Forestry

Logging consistently holds the title for the most dangerous job in the U.S. It’s a harsh mix of massive weights, unpredictable trees (“widow-makers”), and steep, slippery terrain.

The shift in the trees is all about Mechanized Harvesting. We’re starting to see a surge in winch-assisted machines that can climb slopes where workers shouldn’t ever be standing. Instead of a guy with a chainsaw on the ground, we have operators inside reinforced, pop-up control cabs using hydraulic jaws to fell and delimb trees. This field is also using LiDAR drones to map the forest floor in 3D. They identify ‘dangerous’ trees or even unstable ground before the crew arrives. Saving time and lives.

Commercial Fishing

The ocean doesn’t care about you… At all. Between the harsh weather, rogue waves, and heavy machinery on a constantly slippery deck, commercial fishing is a literal nightmare for safety stats. It’s one of the most dangers jobs, with fatality rates hitting over 25-30 times higher than the average worker.

Now there are “Smart Boats.” AI-integrated nets and automated winches take the “brute force” out of the job. Tiny sensors in the nets alert workers exactly when to haul in, cutting down the amount of risky “emergency” maneuvers. Wearable technology (like man-overboard alarms that immediately ping GPS and deploy life rafts) is becoming the industry standard. Commercial fishing is finally bringing 21st-century tech to one of the world’s oldest (and still deadliest) professions.

Roofing and Construction

Gravity sure is a relentless force. Falls are the leading cause of death in construction overall, but roofers are up there near the top of the list.

The fix? Drone-First Inspections. Most projects now start with a drone doing the measurements and damage assessment. This keeps workers off the roof until the actual work starts. For the construction, we’re seeing a big rise in prefabricated modular roofing. Instead of piecing a roof together shingle-by-shingle at 40 feet in the air, whole sections are built, safely, on the ground and craned-up into place. The best way to beat gravity is to not challenge it.

Pesticide Crop Dusters

Flying a tiny, aging plane twenty feet above a field while spraying chemicals is a double-edged sword. You’ve got the risk of a low-altitude crash mixed with the long-term health effects of breathing in those chemicals.

This is being phased out… Large-scale agricultural drones are taking over field mapping and chemical application with surgical precision. It’s safer for the pilot (who is now on the ground) and better for the environment because we aren’t just “blanket spraying” everything. It’s a win-win that has pulled another profession off the most dangerous jobs list.

Bomb Disposal

It used to be that if you were on a bomb squad, your main “safety gear” was just a thick suit and a very, very steady hand. The job is still around, but it has been completely reoutfitted.

Modern bomb squads lead with robotics. They send in a treaded robot with a multi-axis arm, like the L3Harris T7, to do the poking and prodding. If something goes wrong, we lose a few thousand dollars’ worth of hardware instead of a life. The technicians have become so advanced that the disarmer is essentially a remote pilot.

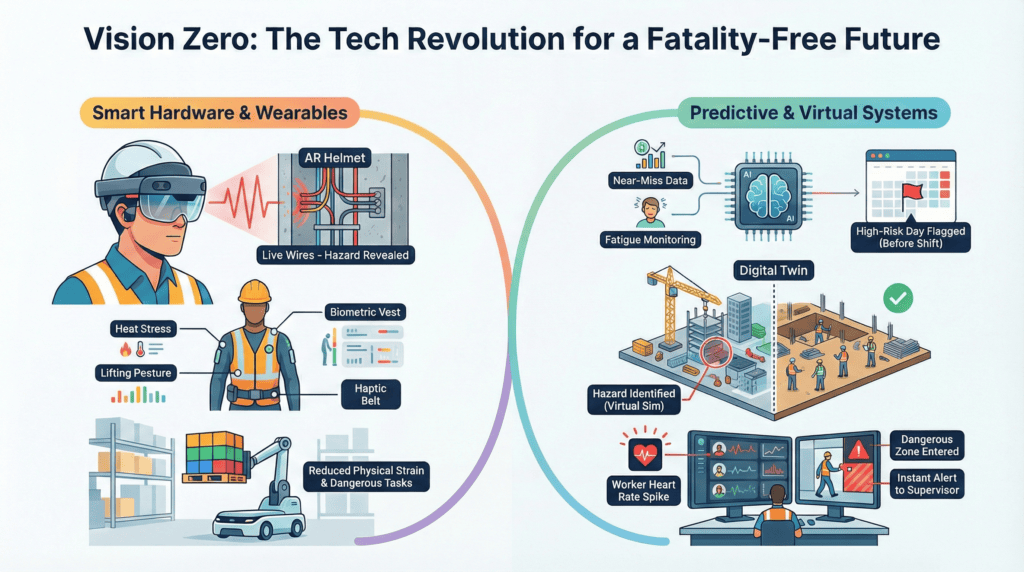

The Path to Zero

The goal is no longer just “fewer” accidents. We’ve moved into the era of Vision Zero. This isn’t just a catchy name; it’s a radical shift in philosophy that started in Europe and has since become the gold standard for global safety. It’s based on one premise: Human error is inevitable, but death and serious injury are not. Especially for workers in some of the harshest places on the planet, like Antarctic Jobs.

Here is the breakdown of the who, what, where, when, and how of the push to make the “fatality budget” a thing of the past.

Who is Leading the Charge?

It’s an all-around effort. OSHA has pivoted its agenda toward high-hazard transparency. They aren’t just looking for rusty ladders anymore; they are using data to shame companies with high injury rates into compliance.

But the real “who” is the workforce. Gen Z and the upcoming Gen C are the first generations to treat physical and psychological safety as non-negotiable. They aren’t interested in the “tough it out” culture of their parents. They want tech that works, and they’re moving to companies that prove they care.

What are the Tools of the Trade?

The “What” is a mix of high-end hardware and smarter software.

- Predictive AI: We now have systems that analyze years of “near-miss” data. If the weather is weird, the crew is tired, and the equipment is past its service date, the AI flags a “high-risk day” before the shift even starts

- Smart PPE: We’re seeing “Biometric Vests” that track heat stress in real-time and “Haptic Belts” that buzz when a worker uses a bad lifting posture

- Psychological Safety: For the first time, mental health is an official pillar of safety. 2026 is the year where “burnout prevention” moved from the HR office to the safety manual, recognizing that a distracted or stressed worker is a high-risk worker

Where is This Happening?

It’s everywhere. It’s not just the oil rigs and the logging camps. This revolution is hitting warehouses, where autonomous robots handle the heavy lifting, and even construction sites, where AR (Augmented Reality) helmets show workers exactly where the “no-go” zones and live wires are located behind a wall.

When Will We See Results?

The industry has set its sights on the “2030 Roadmap.” This is the target year for most global industries to cut preventable workplace deaths by at least 30%. We are currently in the “implementation phase,” where the tech we’ve discussed is moving from expensive prototypes to mandatory equipment.

How Does it Actually Work?

It works by shifting from Reactive to Proactive. In the old days, a worker fell, and then the company bought better harnesses. Today, we use “Digital Twins,” virtual simulations of a job site, to find hazards before the first brick is laid. We use real-time monitoring that alerts a supervisor on their tablet the second a worker’s heart rate spikes or they enter a dangerous area. We are finally learning to predict the accident itsefl, instead of just documenting it.

An Endangered Species

We are standing at the edge of a historical shift. For centuries, we just accepted that a certain number of lives would be the “cost of doing business.” We built the modern world with a built-in “fatality budget.”

That budget is being closed by equal opportunity employers. Between AI that “sees” danger and a culture that finally values the person over the process, the most dangerous jobs are losing their teeth. We aren’t just making work safer; we’re making the “deadly job” an endangered species.