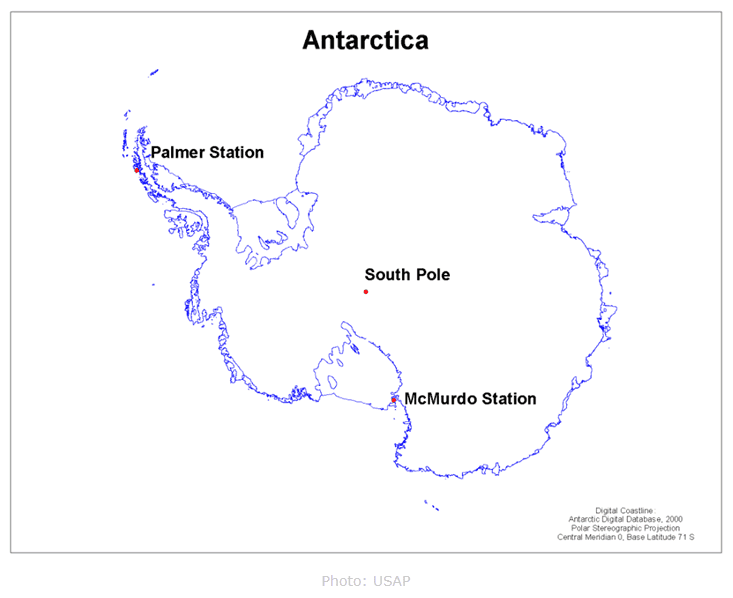

Ever thought that Antarctic jobs are only for scientists or the military? There’s no regular jobs there… right? Think again! There are many more jobs available there than just scientists. The United States Antarctic Program keeps three permanent stations running down at the bottom of the world.

McMurdo Station is on the southern-most tip of Ross Island and is basically the main hub for flights, personnel, and cargo. Inland is Amundsen-Scott, it’s planted right at the literal South Pole. And finally, off the Antarctic Peninsula sits the Palmer Station on Anvers Island, it’s the only U.S. base that happens to be north of the Antarctic Circle.

Fun Fact: Palmer Station is technically closer to South America than to the South Pole.

Scientists and researchers may rotate in and out, but base-life depends on a whole different group of people. Electricians fix wiring while it’s fifty below, Chefs and Cooks feed everyone three times a day, and mechanics might rebuild engines that freeze solid overnight. Each of the station’s success relies on tradespeople, technicians, and logistics staff. There are real jobs available there with set schedules, strict procedures, and a community that functions more like a small town in one of the harshest workplaces on Earth.

Map of Antarctica highlighting McMurdo, South Pole, and Palmer Stations: the three primary U.S. research bases operated by the U.S. Antarctic Program.

Why there is steady hiring:

- Deployments are seasonal, so experienced people rotate in and out every year.

- Projects change and expand, so contractors open up new positions.

- A portion of workers “winter over,” then take a long break, creating fresh vacancies.

Most work contracts cover almost everything you need once you’re in. You’ll get round-trip travel, housing, and three solid meals a day while you’re working on the ice. The employer will issue all the heavy cold-weather gear you’ll need, and many departments offer overtime when projects run long.

Over time, crews tend to become their own community. People usually come back season after season just to work with the same people again.

Where You Might Go

Stations and gateways

- McMurdo Station (Ross Sea): The largest and busiest of the three bases. It’s basically the headquarters for the U.S. in Antarctica. Almost everything goes through here. Crews will usually stage in Christchurch, New Zealand, first, where they do orientation, pick up their cold-weather gear, and wait for a clear-sky window to fly in or the season.

- Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station: You can only reach this one by flying out of McMurdo on a ski-equipped aircraft… when weather allows. The crew here is smaller and more tightly specialized. The engineers, mechanics, and scientists handle everything from instruments to power generation to keep the Pole running through months of darkness.

- Palmer Station (Antarctic Peninsula): This one is the smallest of the three and the only one you can reach by sea. Most people meet in Punta Arenas, Chile, before sailing down. The work here is mostly marine-based and small-vessel operations. It runs a close-knit crew that lives almost shoulder-to-shoulder through the season.

Season windows (typical)

- Austral Summer (Primary Hiring): Runs from October through February roughly. It’s when most crews deploy, because temperatures are bearable and daylight lasts nearly 24 hours. If you’re applying for your first contract, this is the best window to aim for.

- Winterover (Advanced/Limited Hiring): From February to around October though, only a handful of people stick around. The bases go quiet, supply flights stop, and the team settles in for months of isolation. Because there are almost no flights in or out, these crews go through extra mental-health and resilience screenings before being cleared.

Work weeks can be long, but they’re structured. The common pattern in summer rotations is six days on, one day off, with overtime depending on project load and department policy.

Who Actually Hires (and Where to Apply)

The National Science Foundation funds the science side of things down there. However, private contractors hire most of the support staff. Each season, multiple companies post openings for the same stations and share the hiring responsibilities.

Start with:

- USAP Official Portal: This should be your first stop: [https://usap.gov] → “Jobs & Opportunities” → Find a job you want to apply to, and go for it!

- Prime and Partner Contractors: Look for listings from firms that handle Antarctic support (examples you will often see are: logistics/engineering; food services; aviation support; environmental services; custodial; carpentry and trades; fire and medical).

- Science Support & Universities: A few occasional postings for field assistants, mountaineer guides, lab technicians, or marine crew may appear on university job boards if they’re tied to funded projects.

Bonus Tip: Create a saved search for “Antarctica,” “McMurdo,” “South Pole,” and “Palmer” on major, niche and even diversity job boards, then apply directly through the contractor’s site so your application is submitted correctly.

Jobs, Paths, and Where Beginners Fit

Below are some common categories that can get your snowshoe in the door. Each station structures their teams a little differently, but this is the gist of it:

Trades and Utilities

- Electrician, plumber, carpenter, sheet-metal worker, welder, power plant mechanic, fuel systems technician, boiler operator.

- Ladder: Helper → junior → lead → supervisor. Prior commercial or industrial experience travels very well in these positions.

Fleet, Vehicle, and Heavy Equipment

- Heavy equipment operator, heavy shop mechanic, light vehicle mechanic, preventative maintenance, fuels, runway grooming.

- Ladder: Operator or technician → lead → foreman. Experience with cold-weather starts, hydraulics, and diesel systems is highly valued.

Cargo, Supply, and Logistics

- Cargo handler, materials coordinator, warehousing, vessel offload support, waste handling and recycling.

- Ladder: Assistant → coordinator → supervisor. Safety, forklift, and inventory systems experience help you move fast in these jobs.

Food Service (Galley)

- Production cook, baker, dining attendant, food safety and sanitation.

- Ladder: Attendant → cook → lead → chef. This is one of the most realistic entry points; many people start here, then switch departments in later seasons.

Information Technology and Communications

- Help desk, network technician, radio and satellite communications, electronics technician.

- Ladder: Technician I → tech II → senior → site lead. Hands-on troubleshooting plus documentation habits matter more than brand-name certifications, but the latter never hurts.

Medical and Emergency Services

- Paramedic, physician assistant, nurse, fire department, environmental health and safety.

- Ladder: Thes jobs vary by license. Winterover medical roles require extra screening and really strong documentation skills.

Science Support and Field Safety

- Field technician, lab assistant, mountaineer guide, marine technician.

- Ladder: These are competitive spots; prior field work, backcountry safety credentials, small-boat handling, or laboratory experience will make the difference.

How to Pick an Entry Door: If you have limited experience, target galley, cargo/supply, or custodial first. Your goal should be to just get on the ice, then build your reputation, THEN ladder into trades, vehicles, or IT for the next season.

Minimum Requirements and Pre-Screening

Background: Standard employment/reference checks and drug screening.

Medical (“Physical Qualifications”): Comprehensive physical, bloodwork, immunizations, and dental clearance. In some cases age-based tests (for example, EKG) might apply. As mentioned before, Winterover candidates have to complete additional psychological screening.

Travel Documents: You’ll need a valid passport and no unresolved legal restrictions.

Work Eligibility: you must be authorized to work for the hiring contractor (U.S. citizens and permanent residents for most roles).

Safety Expectations: training in hazard communication, lockout/tagout, confined space (depending on job), and environmental protocols is the norm.

Pro Tip: Gather your medical and dental records before you apply so you can move quickly through the process when the contractor sends the physical-qualification forms.

Application Timeline

Hiring for Antarctic jobs follows a seasonal rhythm, and understanding it helps you time your application before competition floods in. Use this as a planning template; actual dates vary by contractor and department.

- April–July: The first wave of summer postings begins to appear on contractor websites and on Usap.gov. This is when to start applying, even if you’re not sure which job fits best yet. Entry-level jobs like dining attendant, cargo handler, and janitorial support usually open first. Submit multiple applications, because each station hires separately.

- June–August: Contractors begin interviews and issue conditional offers. This is also when medical and background screening starts. Respond quickly, some applicants lose their slot by simply waiting too long to book their physicals or send dental forms. If you’re planning to winterover, you’ll begin additional psychological evaluations around this time.

- September: Travel logistics and staging details are finalized. Most crews receive deployment packets that include flight schedules, hotel information for Christchurch or Punta Arenas, and instructions for cold-weather gear issue at the Clothing Distribution Center (CDC). Expect frequent updates as weather windows change.

- October–November: Deployment begins. Crews fly to their gateway cities for orientation, gear fitting, and safety briefings. Flights south to the ice run as weather allows, sometimes right on time, sometimes delayed for days by storms or fog. Once you land, you’ll go through on-site safety training before starting regular work shifts.

- February: The austral summer season wraps up. Most contracts end around this time, and return flights begin as weather permits. A smaller group of winterover staff remains behind to keep essential systems running until the next season begins.

- Winterover Applicants: If your goal is to stay through the dark season, plan ahead. You’ll typically accept your position earlier in the year, complete extended psychological screening, and commit to staying until the following spring, when the first flights resume.

Getting a job in Antarctica isn’t a once-in-a-lifetime lottery. You now know roughly when postings appear, how long background and medical checks take, and what to expect before you apply. The challenge is separating yourself from the crowd of applicants without sounding like a tourist… And up next, we’ll look at how to do exactly that.

How to Stand Out

Station managers read through hundreds of applications every season. They look for people who are calm, reliable, and comfortable with routine. Two pages is plenty for a resume in this industry.

Write it for the Work, Not for the Internet:

- Replace “managed cross-functional initiatives” with “kept [equipment/process] running to schedule during long shifts; documented each step for the next crew.”

- Lead with your hands-on experience, it carries much more weight than just job titles.

- Add a tiny “Documentation” line: maintenance logs, checklists, turnover notes, or incident reports you have kept.

Attach Something Tangible:

- Field Operations Readiness Checklist, one pager with gear, maintenance checks, communication plans, and a signature line.

- Cold-Start Procedure if you are a mechanic.

- Small-site Network Troubleshooting Flow if you are an IT technician.

- Food Safety Line Check if you are a cook or dining lead.

Outreach Note to a Recruiter or Supervisor:

“Hello [Name], I’m applying for the [role] for the upcoming season. I have [x] years of [trade/role] and attached a one-page checklist I use to keep work predictable during long shifts. If there is a preferred starting point for first-timers, I am happy to start there and earn my way up.”

Pay, Overtime, Travel, and Taxes

Money isn’t the only reason people head south, but it’s one of the reasons they stay season after season. The pay is steady, the expenses are minimal, and for a few months you can stack nearly every penny you earn. Still, the details matter, and they can vary from one contractor or job to the next.

- Pay: Rates differ by contractor, job type, and season. Many official job postings list a pay range. Use those as your baseline rather than old numbers on a blog. Skilled trades, technical specialists, and winterover positions generally pay more due to workload and risk.

- Overtime: Very common during the austral summer when construction, cargo, and maintenance projects run around the clock. Expect long days during peak operations, especially at McMurdo and South Pole, where daylight lasts 24 hours.

- Room and Board: Housing and meals are included on station. With only a few ways to spend money, disciplined workers can save several months of income in one season. Some people use it to pay for travel between contracts or to pay down major expenses at home.

- Per Diem: Usually not paid while on station, since food and lodging are already covered. Verify this detail before signing; a few specialized or short-term contracts handle expenses differently.

- Travel: Contractors book and pay for all your travel to the gateway city where you’ll receive your issued cold-weather gear and go through orientation and safety briefings before flying south.

- Taxes: You’re typically going to be classified as a W-2 employee, meaning taxes are withheld like normal. If you freelance or work seasonally between contracts, check with a tax professional to handle your deductions correctly. The foreign-earned income exclusion does not apply to Antarctica, since it technically isn’t a foreign country.

In short, you can make really great money working at the bottom of the world. Between free housing, steady meals, and the very few spending opportunities (Snacks, soda, alcohol, cigarettes, decorations, toiletries, etc.), many returning workers treat a season in Antarctica as an adventure and a financial reset.

Life on Station

The actual job description, what tools you’ll use, who you’ll report to, and how the shifts rotate will be laid out clearly in your contract. What rarely gets talked about is what life feels like in between those shifts. Days off exist, but “off” is relative when you live where you work.

- Housing: Dorm-style living, usually shared, with quiet hours and a mix of personalities. The rooms are practical, not fancy, but they’re usually warm and well maintained. You’ll get to know your neighbors fast. Most stations also post weekly cleaning and etiquette guidelines, to keep order.

- Food: Every station has a galley with set mealtimes. Variety depends on shipments and season… Fresh fruit feels like a holiday. Cooks and bakers become legends down there, and mealtimes turn into the main social events of the day.

- Internet and bandwidth: Connectivity is limited and managed very carefully. Personal use is scheduled in specific windows, and download speeds are slow by design to keep systems stable first. Many workers preload their entertainment before they deploy and save their big uploads for home.

- Community: There’s a lot more of it than people might expect. Libraries, gyms, trivia nights, and small clubs pop up all the time. At McMurdo especially, recreation spaces shift as buildings change, but there’s always something happening after work hours.

- Weather: Wind and cold run the show. You’ll learn to layer, label, and check your gear before every step outside. “Safety call” isn’t a suggestion… it’s a rule everyone respects, no matter rank or experience.

- Mental health: The work is steady and meaningful, but also repetitive. Routine helps. So do exercise, small creative projects, and friendships. The people who really thrive treat each day like part of a long-distance trek: steady and sustainable.

What Else You Should Pack

You will receive your Extreme Cold Weather (ECW) gear at the Clothing Distribution Center before you fly south; parkas, insulated boots, mitts, and the all rest. But personal comfort items make a big difference during long deployments. A few small choices can turn a boring bunk into a comfortable space.

Clothing and Gear

- Two sets of thin wool or synthetic base layers for your rotation.

- Enough broken-in, non-cotton socks for your first two weeks.

- A compact headlamp or clip light with rechargeable batteries, darkness lasts a long time.

- A small travel humidifier bottle or nasal saline, the air is painfully dry. Antarctica is a desert after all.

- Lightweight gloves for indoor work where ECW gear can be too bulky.

Personal and Downtime Items

- Laptop or tablet pre-loaded with movies, e-books, and offline work files.

- A few shareable things help too: cards, small games, snacks, or your favorite instant coffee or tea.

- Any vitamins or personal care items that you prefer, since store supplies are very limited.

- Extra glasses or backup lenses; contacts can be difficult to keep lubricated in low humidity.

Pack light but practical. Power outlets and storage are limited, and anything that needs constant charging or special care becomes more trouble than it’s worth. Many veterans bring a few photos, a good notebook, and something creative to do in quiet hours. Those simple comforts go a long way.

Safety, Risk, and Why Procedures Matter

Antarctica rewards people who respect procedures. Checklists, radio calls, buddy systems, and job-site briefings are how teams stay alive when help is a continent away. It’s survival.

Every task, from fueling an aircraft to walking between buildings in whiteout conditions, follows a strict plan. Once you get that rhythm, the rules stop feeling so restrictive and start feeling protective. People who thrive are the ones who like structure and take pride in executing even the small steps right, every single time.

If you naturally document your work, build a quick checklist before you start, or double-check that a lockout tag is in place, you’ll fit in immediately. The culture values calm professionalism over bravado, and that’s part of what makes these teams work so well.

After Antarctica: How to Leverage the Experience

Finishing a season on the ice changes the way hiring managers see you. When an employer reads “McMurdo Station” or “South Pole” on a resume, they know two things instantly: you show up, and you follow the plan.

Alumni often move into emergency management, remote logistics, industrial maintenance, maritime operations, data-center facilities, or energy. The habits built in Antarctica, documentation, teamwork, and composure under pressure, translate directly to those fields.

Before you leave, document what you did: take a few photos (where allowed), write a short summary of your responsibilities, and save one example of a checklist or procedure you built. That becomes a professional artifact, a small proof that you can handle complex work in difficult conditions.

You’ll come home with more than a just paycheck or story. You’ll have a credential that clearly says you can handle just about anything the world throws your way.